It’s been a while.

Mount Rinjali is a volcano in the Indonesian island of Lombok, a little patch of paradise about 60 miles north-east of the better-known Bali. A Greek couple I know, when I told them I’d me in Indonesia, told me in no uncertain terms that I had to (a) climb Rinjali and (b) use the tour company authentic-lombok.com to do so. Being an obedient person, I did. I also brought along some friends from danabijak, a company I’m helping out (or, at least, that I hope I’m helping out).

Here’s RInjali;

Rinjali’s the mountain on the left. “A monster of a mountain,” our tour operator told us. “You will never forget it,” he added (several times). And, not one for hyperbole, “this mountain is different to all other mountains.” We were heading to the crook more or less above the hat of the man in the middle of the above photo on the first day. Early in the second morning, in time for sunrise, we would head up the steep bit and along that nice, gentle ridge on the left to the top.

The first day was not difficult climbing, though we did ascend almost 2000m. What made it difficult was the rain:

Those are the porters, who wandered up in flip flops carrying 20+ kilogram loads on poles while I huffed and puffed my way up with a mere 9 kilogram rucksack designed to distribute the weight properly. I was thoroughly wet by the time I arrived at the rim of the crater, and the clouds meant that there was no view. However, by sunset, the weather cleared and we were treated to this:

Not much to it. A tough day’s hike to be sure, but no aches and pains. And only 1000m up the little steep bit and that long but gentle ridge. So much for being a monster mountain.

Oh dear.

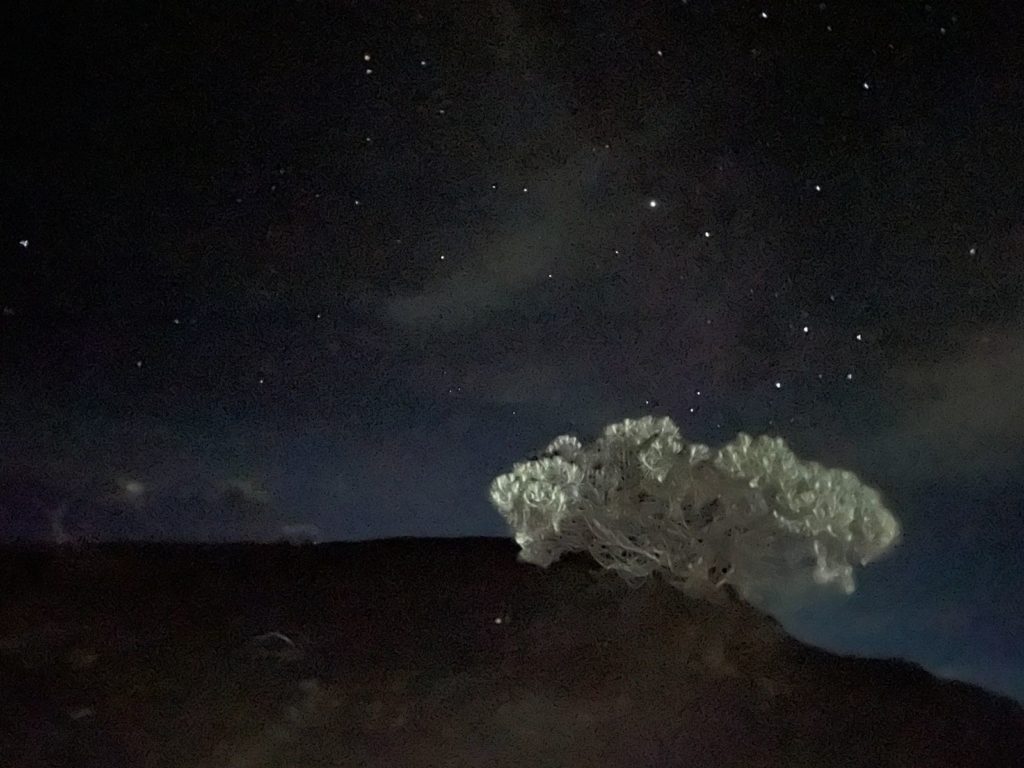

We did get a stunning night sky – and a little plant in the view – but I didn’t have much time to enjoy it. That steep slope was basically a sand dune, that gentle ridge had a sheer 1000m drop to one side – invisible in the darkness – and that little blip of a summit was a one in one slope of volcanic sand that was so fine that our guide advised us to wear a mask. On top of that, we’d had no time to acclimatise to the height, and every step was a deep, deep breath. One hour passed and another, and the summit seemed no closer. Dawn broke in the east, and the summit was as distant as ever. Our party had already separated into the sprinters and the plodders and I was the plodder.

That red dot is me and the photos taken by our semi-professional cyclist and CTO, who was first to the summit an hour before he took that – and it took me another 20 minutes from there to the top.

The guide, Naswar, in the top photo, had barely broken a sweat – and wasn’t drinking or eating because Ramadan had started. He’d ascended the mountain two hundred times already and, although with covid this was his first ascent in three years, he bounded up it. He was, by the way, brilliant. Conscientious and courteous, and somehow able to look after what amounted to a herd of cats.

For me, this was the first ascent ever I had to force myself to complete. There were several parts on that final ascent where I thought about turning back, where I paused looking up and wondered if I could make it and whether I wanted to. Two of our group didn’t make it to the top, having reached their limits and I was a hair’s breadth from being the third.

And then there was getting down.

The reason we’re not standing up straight is that none of us could. It’s been five days now, and I’m still limping.

Was it worth it? For all of us, in different ways, yes. The two who didn’t make the summit were on their first ascent ever of anything big, and they were chuffed pink to have made it as far as they did. The rest of us arrived in reverse order of age. We all struggled with the thin air, the slipping and sliding, the two steps forwards and one slide back. And, yes, we didn’t spend much time on the top and barely looked at the view – which was amazing. But it was worth it.

Plastic

The one thing that let the hike down was plastic waste. Apparently there was a major clean-up on the mountain three or four years ago and whoever did it was thorough, but by the time we arrived, there was plastic litter everywhere.

Our tour guide blamed the mess on the unlicensed operators. Rinjali National Park has (he told us) 17 entrances and six rangers, so lots of groups come in illegally and are not fussy about cleaning up the mess. But the curse of plastic is hardly unique to Rinjali, and the usual “take it home” and “what goes up the mountain comes down” goes only so far. We all drop things, have weak moments, and the monkeys steal lots of stuff and disperse the plastic.

The problem is that humanity is hooked on cheap, plastic packaging. Go into any organic store and you’ll see shelf after shelf of the stuff. Look for an energy bar or snack which isn’t packaged in plastic and you’ll seek in vain.

The sad thing is how unnecessary this is. For most of humanity’s existence, we didn’t have plastic, but we were able to carry snacks up hill and down dale without it. Nasi Lemak is a traditional energy snack and is traditionally served in a pandan leaf; otek-otek is the same. In England, cheese was wrapped in muslin cloth. It’s not as if we have no choice; it’s that we’re too lazy to.

So, my challenge to me for my next main hike is to do it with no plastic at all. Let’s see how that goes…