“What are you trying to prove?” asked a friend of my latest Himalayan trek, the Manaslu Circuit. It’s a fair question. Yes, I’d like to summit a 6,000m / 20,000ft peak, probably Island Peak, but I’m not at the stage of becoming an Eight-thousander (of which more below…) Well, not yet. But, for an answer, read to the bottom.

My partner in pain was again DC – short for Diamond Card, which sums up his lifestyle – and our guide was Hari. Our porter was Sorach – 4’3″ and I doubt he weighed as much as me with our bags, but, as our bags included two bottles of dietary supplement (whisky), I carried his rucksack. This slowed me down and speeded him up, so that worked well. We again (quick plug because they’re nice guys who started from nothing, as well as because they do a good job) used Outfitters to arrange everything, and they again did an excellent job.

The Manaslu Circuit was very different to Ama Dablan Base Camp. At 288km total distance, including excursions, it was equivalent in distance to a marathon every two days for two weeks; at a total ascent of 7,500m it was, in Scots terms, a Monro starting from sea level every two days. All things considered, Ama Dablan was a stroll.

This trek was also much more social. The Khumbu (Everest) region is a superhighway. The only conversation we struck up was with a fellow who’s been going there every year for the past twenty years, for many of which he’d taken groups of schoolchildren. This trek was much less crowded, and most parties of trekkers moved at about the same speed: we met a group of four Slovakians, a pair of ladies from the UK who struggled, a pair from Australia who seemed far too casual but outpaced us, four Danes who looked the part of Vikings, a married couple the husband of which had dashed from the wedding ceremony to ascend a 7000m peak near Sagarmatha, and various others. This may make it seem crowded but, to the contrary, we were on our own for most of the trail. We met – and re-met – the groups at “tea houses” – the hostels on the route – night after night, as we ascended.

The bottom reaches were full of road construction with the consequent dust, noise and litter, so had little to offer. This fine sight greeted us on arrival at the second night’s town:

However, once in the conservation area, the litter all but vanished. While I don’t absolve trekkers from the mess, it became clear that the construction workers were as, if not more responsible as us.

For the next two days, we progressed through one layer after another of desiduous and pine forests, rhododendron forests, of barren high-altitude valleys; of Tibetan villages beneath towering peaks. It rained for much of the way up, and I am not a good enough photographer to capture scenes in the rain, So here’s a flower:

A warning. On the first day of rain, a trekker got ahead of his guide and took a wrong turn. Realising his mistake, he turned back, slipped on the muddy path, and fell to his death in a gorge. This was at well below the 3,000m at which Acute Mountain Sickness sets in. Mountains are dangerous places.

A day or two later, I topped a rise and saw this.

I stood, stunned. Even if we had to turn back, that view made it worthwhile.

From there, our home of the next two nights, Samagoan, was an easy two hours away. The mountain from which the trek takes its name was wreathed in cloud when we arrived, but popped out the next morning: .

That being a rest day, we took a side trek to a monastery. On the way there, I saw an avalanche on the lower slopes of Manaslu and was very glad to be on the opposite side of the valley. Here’s the monastery – not open until summer.

Here’s a pleasant place to spend a few years seeking god,

And here are DC and Hari, on the way back.

On return to town, we came across a puja. There were bells and gongs and drones, and the villagers came out to present the headmen with kata, white silk scarfs used to show respect.

For some reason, DC and I were deemed worthy of respect, draped with white scarfs, and offered a small taste of the local hooch. The puja, we were told, was to distribute rice to the villagers, and I assume that the village heads are those on the ground being thanked for contributing that rice. Later that evening the temperature plummetted, the rain started, yet the villagers were unfazed outside, distributing rice as we huddled inside drinking our whisky (Hari told us that garlic thins the blood which is good for altitude; I hold that whisky does the same.)

The rain turned into snow and the next day’s walk was through a winter wonderland:

It was a short day to our next stop, Samdo, so DC and I headed up the nearest hill, taking the steepest route up. Having got as far up as we wanted, we struck out to traverse down, only to become ensnared in juniper bushes (very much like heather). That took some navigation – the blob is DC struggling to remain attached to the hill.

We got back to bad news. The weather was forecast to set in and, although we’d planned to spend two nights in Samdo, Hari recommended a single night and an attempt on the high point of the trek, a pass the morning after that, a day earlier than scheduled. Although I’d hoped to take a side trek to a glacier, prudence (DC’s mostly) won the day, so we set off the next morning to the camp.

That walk was uneventful and quick, so that afternoon we popped up a hill behind it for the view of the pass. It’s in the middle of the photograph, a long way from where I took it. A very long way.

On the way down, I got talking to one of the Slovakian group :

`Oh, Peter’s here to do his sixteenth eight thousand meter peak.’

`Um,’ said I, `there are only fourteen such peaks.’

`Yes.’

`You mean…?

`Yes, after this he’s going to ascend Everest, come down to 7,000m for a day, then ascend Lhotse. Two 8,000m peaks in three days.’

What was a trek to us was training for Peter. (I thought at the time that only Reihhart Messner and Andy Hinkes had summitted all fourteen of the world’s 8,000m peaks, but post-trek I found out that a few dozen people have managed the 14 – and you’ll find Peter’s name on that list. That leaves 7 billion, myself included, who haven’t.)

After a crap night’s sleep, due to a rucksack that refused to play pillow and a tent pitched on an incline, at 4:00 a.m. we started up the pass. My camera isn’t good enough to capture the stunning beauty of the night sky at altitude, but it’s good enough to capture the dawn:

And here we are at the top, with me squinting in the sunlight.

Then ascent, through fresh snow, turned out to be the easy part. We had a 1,500m descent down the other side of the pass, over steep snow, without crampons or ice axes, leading out on to a glacial moraine, and more steep stuff, with not a tea house in sight. By the time we arrived at Bimtang, that first Gorkha beer went down very fast.

That was it, we thought. A three or four day trek back down and we’d be off to Kathmandu. We hadn’t counted on the weather dumping four inches of snow overnight; and the next day was, in the word’s of one of our Vikings, “This is the best ever!”::

Rhododendrons were in bloom:

As we descended, it got greener and greener.

So; why the title of this blog? As I mulled on Peter’s massive achievement, it struck me that, at the end of the day, bagging peaks is not so very different from bagging the “big five” African game animals, the “Seven Summits” and all the others. But does it address this?

That’s Samagoan, where we spent two nights. I do not mean this in a derogatory way, I do not mean to allocate blame, and I have no reason to believe that the villagers are unhappy. But the squalor is Medieval. Here’s a town we saw further down, where the end of our trail joins the beginning of the Annapurna circuit:

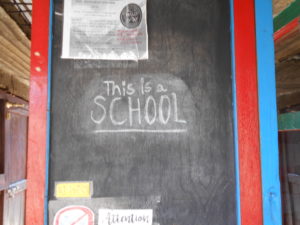

That’s US$450 they’re asking for. Over 100,000 trekkers pass that way every year, every single one of whom has spent more than that to trek. And this sign probably says it best

That’s Samagoan’s school sign. There is no other. So what do I hope to achieve? That you, reader, will chip in to my friends at Room to Read, who are doing their best for schools in poor countries..